In our last talk I was trying to explain what training in Zen Buddhism does to change human consciousness, and I showed that it takes away our ingrained tendency to block ourselves in thought and action by the mechanisms of self-consciousness. It doesn’t mean that a person can’t be self-conscious anymore, that he can’t think about what he has to do and how to control himself. But he no longer experiences his observing self—you know, the self that says, “What will other people think? Do I make sense? Am I right?”—he no longer senses this as an obstacle. And he receives training in acting spontaneously rather than deliberately. And, as I pointed out, that is a way of action which we are not ordinarily taught. All our education consists in knowing how to act and think deliberately, and this gives a certain stickiness or artificiality to everything that we do. But when he has been put through this training—which involves a kind of dying to himself; that is to say, he gets in a situation where he’s faced with an unanswerable question, the kōan, the Zen problem for meditation, and all his wits are exhausted in trying to answer this question; the question being, in effect, however it is phrased, to perform a perfectly spontaneous, genuine, natural act: express your true self. And nobody can do that intentionally.

You know, there’s a proverb in India that if you think of a monkey while you’re drinking medicine, the medicine doesn’t cure you. So imagine a person trying not to think of a monkey while taking medicine. Well, that’s the sort of bind we get into when we try, intentionally, to be natural. And it’s only when all our intentional wisdom, our contriving wisdom, is frustrated and brought to an end—brought to a kind of death, at any rate temporarily—that a completely genuine action is possible. As a Western saying goes: “Man’s extremity is God’s opportunity.”

Now you might raise the question: how does a person express this kind of freedom? I finished last time on the note of the Zen student being as free as the clouds and the water: the image of the clouds drifting unobstructedly through the sky, the water flowing on, always taking the line of least resistance, but always overcoming even the hardest obstacles. If a person acts without inner conflict and he acts with true spontaneity, how does he act? What does he do to express himself?

And I think one of the very best examples of this is from the influence of Zen upon Far Eastern painting. The art of China and Japan has been very, very profoundly influenced by Zen. Now, I suppose most of you know that Chinese painting is intimately connected with Chinese writing, which was originally a pictographic language. You can, for example, here how, at the top left, the pictogram of mountains has become the formal symbol written with a brush, which now means “mountain” or “hill” in Chinese characters. It’s pretty obvious how concrete objects can be represented by a pictogram. And it’s interesting to see how abstract ideas can also be conveyed. The next drawing you see there shows at the top right the pictogram of a lizard. And below, the formal brush character, as now written, which means “change,” perhaps because this was a chameleon who changed color according to his background, or perhaps because the movements of a lizard are so slippery and rapid. And then again you can see another abstract idea conveyed. The pictogram at the top shows a mat with a pattern on it. And the formal brush-written character below means “cause.” Because just as a mat is a firm basis for something, so it represents the cause of a certain situation.

Now, every child brought up in China learns the discipline of writing these characters. And to learn, as it were, the alphabet of characters—how, for example, to make a cross stroke, which would look something like a bone. Or he learns perhaps the character which is supposed to contain all the strokes: the character meaning “eternal.” A lot of you have seen this writing and work done by Mr. [Takahiko] Mikami, who’s a real artist. And I don’t pretend to be any great calligrapher, but I’m just showing you that the art of the brush involves endless, endless practice to get these things correct. In other words, I haven’t done this very well here, because the top of this character should be more stubby. But, of course, I’m doing something I shouldn’t really do at all, and that’s touch up.

But just as there is in learning—all the characters are made up of certain basic elements. There are certain basic strokes. This is supposed to involve about seven of them: one, two, three, four, five, six—I don’t know where the seventh is. But in learning these basic strokes which are practiced again and again and again, the person studying Chinese writing acquires, as it were, not an alphabet in our sense, but an alphabet of strokes.

Now, in exactly the same way, in the art of painting, Chinese painting is made up of an alphabet of various strokes that convey various things. And you can see, for example, how the brush lends itself quite naturally to drawing certain forms. If we take, for example, just—well, that’s rather wiggly—but here is the leaf of a bamboo. See? The brush draws them naturally. And it even conveys with the part at the end where the ink runs a little dry the tip of the leaf where it may get a bit ragged. And so, with immense rapidity, all kinds of different sorts of leaves can be drawn with a brush. Little leaves or wisps of grass. And there is a book called The Mustard Seed Garden which is published in this country under the title The Tao of Painting by Mai-Mai Sze, which shows all the formal executions the artist goes through to convey different shapes—clouds, so on—all in accordance with the nature of the brush.

Now here, for example, is a painting by the Japanese artist Josetsu, showing a very masterly study of bamboos. If you look a little bit over to the left of the painting, you can see a spray of bamboos almost just within view. And actually, the painting shows a rather amusing subject. It’s a man trying to catch a fish in a gourd. And this is suggestive of the futile attempt to grasp life in intellectual terms; to catch the mystery of being in words. And, in the same way, there is a Chinese proverb which says: “One picture is worth ten thousand words.”

You see, the problem is: painting is perhaps a little closer to the real world than talking. If I wanted to show you, for example, how to do something rather complex like tying a knot, it would be very difficult to explain in so many words how that knot is to be tied—but in an instant I can show you. And in this way a picture shows us far more than words ever can. And so it’s closer to nature.

But then the question arises: is painting something purely representational? Is it an activity, in other words, in which man confronts nature, looks at it, and copies it? This is a problem that arose not only in the Far East, but also arises today in the world of contemporary art, contemporary painting, which incidentally has felt to some considerable extent the influence of Far Eastern ideas, and particularly of Zen.

Now, very often now we go to our museums and art galleries, and we see something on the walls of which a kind of ordinary Joe says, “That doesn’t look to me like a painting!” No. Because he has expected to see a representation of something. He’s expected to see the artist do by hand what the camera does mechanically. And it doesn’t strike him that a painting does not have to be a picture. It doesn’t necessarily have to copy nature.

And thus, in the Far East, under the influence of Taoism and Buddhism, there has been evolved what you might call the natural art of painting—or painting considered not as a copy of nature, but as a work of nature. And this has been shown in an exemplary way by artists who were trained in Zen. In other words, they would master a technique by all kinds of careful training, and then, when that mastery of technique—first of all, learning to write Chinese characters, after that learning the basic alphabet of strokes necessary for painting—when they had mastered that technique, they would give themselves up completely to spontaneity.

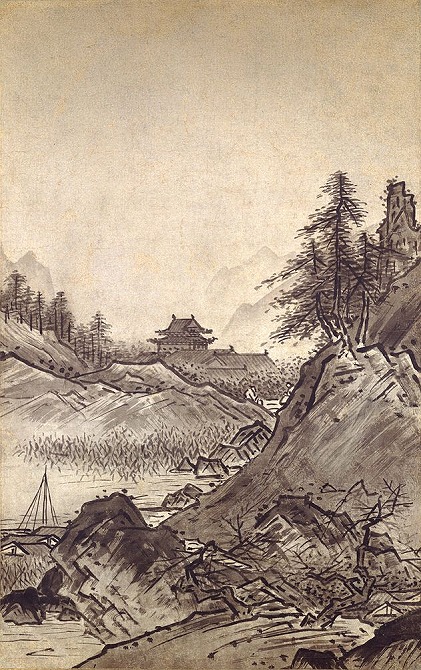

One of the most interesting examples of this is a great Japanese master of the thirteenth century called Sesshū. And if you look closely at this painting, you can see two things. First of all, its undoubted technical excellence. And secondly, if you look closely, you can see its relationship to writing, to the use of the brush for drawing letters—what you might call the calligraphic. Perhaps you know the word “calligraphic” simply means “beauty of writing.” So calligraphy is beautiful writing. But you can see the calligraphic character of this painting. And you can see that Sesshū had the most astonishing technique. I mean, he was no one—like, some people suspect some contemporary artists of being; a person who couldn’t draw and therefore did something formalist instead.

But now, what happens when a man like Sesshū really lets himself go? What is it? It’s not, perhaps, until you begin up the painting a bit and see what lies above that you begin to recognize that this is a mountain landscape. And this is done with incredible speed. Sesshū sometimes, in order to get a kind of rough effect, would use straw with the ink on instead of a brush.

Now, what happens when the same thing is done in writing? The formal character of writing gives way to a purely spontaneous way of writing in what is called “grass style.” Here is a poem which says,

The morning dawns,

But the dusky night follows soon.

So is life like a crystal drop of dew.

Unconcerned, the morning glory goes on,

Blooming, blooming its short yet full life.

Well, I happen to know the translation, but I can assure you that when you get into that kind of grass style of writing which looks almost like the tendrils of the morning glory, a Japanese has almost as much difficulty in reading it as we have.

Now let us consider the medium more carefully with which this work is done. First of all, consider the brush. A great deal of our painting is, of course, done with rather firm brushes with the kind of bristles in use for oil. But the Chinese brush is an astonishingly flexible thing. And notice that it is used with the wrist unsupported. You don’t use it like this and sort of scratch your drawing away, as we do with a pen. Your arm is free. And therefore, as it were, the dynamics of your whole body go into making a brushstroke. And in this way the brush, being so responsive to your slightest motion, reveals character more strongly than anything else.

Next, consider ink. Actually, although this is black ink rubbed from a solid stick of ink, you might say that it’s capable of enormous variations in color. You can mix it with varying degrees of water and show all kinds of depth of black, so that it has tremendous variation. And also here, where the brush runs dry, you get a kind of what they call flying hairlines, which show the motion of the stroke. You know, sometimes, when we want to show motion, and somebody, say, is moving his hand: and here we’ve got an arm, and somebody is hitting somebody over the head with it. Well, to show that the arm is moving we do little things like this—to show: here’s a hammer in the hand, you see? And the hammer is coming down. Well, to show motion we do this. But in this way, motion is shown in Chinese painting and writing by the flying hairlines of the brush, which give a dynamic quality.

Now, another thing that’s very important about the medium for purposes of Zen art is the quality of the paper or silk upon which the painting or writing is done. This is absorbent paper, and therefore you notice that if I don’t draw a line smoothly, but I hesitate, in a little while you will see that becomes an area where too much ink has run onto the paper, and you get a bulge. And therefore, unless you intentionally want a bulge at a particular point, your motion, writing with the brush, must be entirely smooth. There I want it to bulge. And in this sense there is a kind of parallel between painting and life. You know, as Omar Khayyam says:

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit

Can lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

And so, in the same way, the painter or the writer in this medium has to move without hesitation. As our own proverb says, “He who hesitates is lost.” And thus, it involves particularly the quality of what is called in Zen yizhí zǒu: “going straight ahead”-ness, without doubt. And this quality, when it is ingrained in our character through learning to trust our own spontaneity, becomes the greatest instrument of the artist. And the man, in other words, who has that character can—however he goes at this—hardly make a mistake. His character is revealed in everything that he does. And as his action is completely unobstructed, so there is a kind of flowing vitality in all of his work. So, in this sense, the man who is, as it were, dead to himself—there is a Zen poem which says, “While living, be a dead man; thoroughly dead.” And then, whatever you do, just as you will, will be right. So a man who has this becomes a superb artist.

Now, one of the most interesting characteristics of Zen art is its kind of playfulness. Because, you see, a person who has died to himself doesn’t take himself seriously any longer. He has a sense of life—as we say in our own slang—not being any longer a drag. He’s not in conflict with himself. He has already, as it were, given himself up to death. And so here is his spirit in a painting by Sengai, a great Zen master of the seventeenth century, which shows Hotei. You know, you often see him as the so-called fat Buddha. You can buy figures of him in any Chinese artwork store. Hotei. He is a kind of a tramp. And here he’s waking up from his sleep. And the poem written above him on the painting says:

Buddha is already dead.

Maitreya [who’s supposed to be the next Buddha to come in many years] has not yet come.

I have had a wonderful sleep

And didn’t even dream about Confucius.

It seems, you see, a kind of irreligious attitude. For just as the art of Zen is artless art, so the religion of Zen is religion without religiosity. The masters are never drawn in a kind of pompous, sacred style, but always looking more like hobos and bums. This painting is a Chinese painting entitled “Zen master in meditation,” but he looks more as if he was asleep. And this I would call—this drawing of the saint meditating as if he were asleep—a kind of religion of no religion, which doesn’t take itself seriously.

There was once a Zen student who asked his teacher how he was getting along in his study of Zen. And the teacher said, “You’re alright. But you’ve got a trivial fault.” “What’s that?” “You’ve altogether too much Zen,” he replied. “Well,” he said, “if you are studying Zen, isn’t it very natural to talk about it?” “Oh,” he said, “when it’s like an everyday conversation it’s somewhat better.”

And here you see, in another painting by Sengai: it’s an everyday matter. Just blossoms. And yet, this is Zen. Or these marvelous persimmons by the great Chinese Zen monk Muqi. Just persimmons, sitting there in the spirit of what is called, in Japanese, sono mama. It means “just like that.” I can perhaps illustrate the spirit of sono mama by a haiku poem which says:

Weeds in the rice field.

Cut them down

And, sono mama,

Fertilizer.

Or, again Sengai, showing the two Buddhist hermits Hanshan and Shide looking like a pair of idiots. Because, again: just as Zen represents its religion in the secular, its holiness in a kind of fat tramp looking as if he was fast asleep, and its wisdom as the behavior of a lunatic—you see, it doesn’t take itself seriously.

Here is a Zen painter of modern times, Saburō Hasegawa: a self portrait. And the writing underneath is a quotation from Lao Tzu:

The people of the world seem so satisfied,

As if partaking of formal dinner,

As if climbing a terrace in springtime.

I alone am mild,

Like one with nothing to do,

Like a baby that cannot get smile.

Unattached, as if without a home.

The people of the world seem to have everything,

But I seem to have lost everything.

Mine is the heart of a fool.

And here, again, is another piece by Hasegawa. It's a print from an old boat that was washed up on the beach. And the character written over it is “time.” And here, again, you see: in this marvelous arrangement of the natural grain in wood we have the artist expressing, once again, that character I showed you in the last talk, lǐ, which means “the infinitely complex patterning of nature.”

And so it is playing on. And you may ask: what does it mean? What do the stars mean? What does the wind say? Where are the clouds going?